- Home

- Thomas Harris

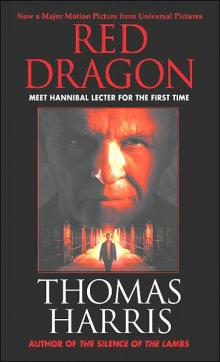

Red Dragon hl-1 Page 11

Red Dragon hl-1 Read online

Page 11

For three hot days he worked in the warehouse where the Jacobis’ household goods were stored. Metcalf helped him at night. Every crate on every pallet was opened and their examined. Police photographs helped Graham see where things had been in the house.

Most of the furnishings were new, bought with the insurance from theDetroitfire. The Jacobis hardly had time to leave their marks on their possessions.

One item, a bedside table with traces of fingerprint powder still on it, held Graham’s attention. In the center of the tabletop was a blob of green wax.

For the second time he wondered if the killer liked candlelight.

TheBirminghamforensics unit was good about sharing.

The blurred print of the end of a nose was the bestBirminghamand Jimmy Price inWashingtoncould do with the soft-drink can from the tree.

The FBI laboratory’s Firearms and Toolmarks section reported on the severed branch. The blades that clipped it were thick, with a shallow pitch: it had been done with a bolt cutter.

Document section had referred the mark cut in the bark to the Asian Studies department atLangley.

Graham sat on a packing case at the warehouse and read the long report. Asian Studies advised that the mark was a Chinese character which meant “You hit it” or “You hit it on the head”—an expression sometimes used in gambling. It was considered a “positive” or “lucky” sign. The character also appeared on a Mah-Jongg piece, the Asian scholars said. It marked the Red Dragon.

Chapter 13

Crawford at FBI headquarters inWashingtonwas on the telephone with Graham at theBirminghamairport when his secretary leaned into the office and flagged his attention.

“Dr. Chilton atChesapeakeHospitalon 2706. He says it’s urgent.” Crawford nodded. “Hang on, Will.” He punched the telephone.

“Crawford.”

“Frederick Chilton, Mr. Crawford, at the—”

“Yes, Doctor.”

“I have a note here, or two pieces of a note, that appears to be from the man who killed those people inAtlantaand—”

“Where did you get it?”

“From Hannibal Lecter’s cell. It’s written on toilet tissue, of all things, and it has teeth marks pressed in it.”

“Can you read it to me without handling it any more?” Straining to sound calm, Chilton read it:

My dear Dr. Lecter,

I wanted to tell you I’m delighted that you have taken an interest in me. And when I learned of your vast correspondence I thought Dare I? Of course I do. I don’t believe you’d tell them who I am, even if you knew. Besides, what parficular body I currently occupy is trivia.

The important thing is what I am Becoming. I know that you alone can understand this. I have some things I’d love to show you. Someday, perhaps, if circumstances permit. I hope we can correspond…

“Mr. Crawford, there’s a hole torn and punched out. Then it says:

I have admired you for years and have a complete collection of your press notices. Actually, I think of them as unfair reviews. As unfair as mine. They like to sling demeaning nicknames, don’t they? The Tooth Fairy. What could be more inappropriate? It would shame me for you to see that if I didn’t know you had suffered the same distortions in the press.

Investigator Graham interests me. Odd-looking for a flatfoot, isn’t he? Not very handsome, but purposeful-looking.

You should have taught him not to meddle.

Forgive the stationery. I chose it because it will dissolve very quickly if you should have to swallow it.

“There’s a piece missing here, Mr. Crawford. I’ll read the bottom part:

If I hear from you, next time I might send you something wet. Until then I remain your

Avid Fan

Silence after Chilton finished reading. “Are you there?”

“Yes. Does Lecter know you have the note?”

“Not yet. This morning he was moved to a holding cell while his quarters were cleaned. Instead of using a proper rag, the cleaning man was pulling handfuls of toilet paper off the roll to wipe down the sink. He found the note wound up in the roll and brought it to me. They bring me anything they find hidden.”

“Where’s Lecter now?”

“Still in the holding cell.”

“Can he see his quarters at all from there.”

“Let me think… No, no, he can’t.”

“Wait a second, Doctor.” Crawford put Chilton on hold. He stared at the two winking buttons on his telephone for several seconds without seeing them. Crawford, fisher of men, was watching his cork move against the current. He got Graham again.

“Will… a note, maybe from the Tooth Fairy, hidden in Lecter’s cell atChesapeake. Sounds like a fan letter. He wants Lecter’s approval, he’s curious about you. He’s asking questions.”

“How was Lecter supposed to answer?”

“Don’t know yet. Part’s torn out, part’s scratched out. Looks like there’s a chance of correspondence as long as Lecter’s not aware that we know. I want the note for the lab and I want to toss his cell, but it’ll be risky. If Lecter gets wise, who knows how he could warn the bastard? We need the link but we need the note too.”

Crawford told Graham where Lecter was held, how the note was found. “It’s eighty miles over toChesapeake. I can’t wait for you, buddy. What do you think?”

“Ten people dead in a month—we can’t play a long mail game. I say go for it.”

“I am,” Crawford said.

“See you in two hours.”

Crawford hailed his secretary. “Sarah, order a helicopter. I want the next thing smoking and I don’t care whose it is—ours, DCPD or Marines. I’ll be on the roof in five minutes. Call Documents, tell them to have a document case up there. Tell Herbert to scramble a search team. On the roof. Five minutes.”

He picked up Chilton’s line.

“Dr. Chilton, we have to search Lecter’s cell without his knowledge and we need your help. Have you mentioned this to anybody else?”

“No.”

“Where’s the cleaning man who found the note?”

“He’s here in my office.”

“Keep him there, please, and tell him to keep quiet. How long has Lecter been out of his cell?”

“About half an hour.”

“Is that unusually long?”

“No, not yet. But it takes only about a half-hour to clean it. Soon he’ll begin to wonder what’s wrong.”

“Okay, do this for me: Call your building superintendent or engineer, whoever’s in charge. Tell him to shut off the water in the building and to pull the circuit breakers on Lecter’s hall. Have the super walk down the hall past the holding cell carrying tools. He’ll be in a hurry, pissed off, too busy to answer any questions—got it? Tell him he’ll get an explanation from me. Have the garbage pickup canceled for today if they haven’t already come. Don’t touch the note, okay? We’re coming.”

Crawford called the section chief, Scientific Analysis. “Brian, I have a note coming in on the fly, possibly from the Tooth Fairy. Number-one priority. It has to go back where it came from within the hour and unmarked. It’ll go to Hair and Fiber, Latent Prints, and Documents, then to you, so coordinate with them, will you?.. Yes. I’ll walk it through. I’ll deliver it to you myself.”

* * *

It was warm—the federally mandated eighty degrees—in the elevator when Crawford came down from the roof with the note, his hair blown silly by the helicopter blast. He was mopping his face by the time he reached the Hair and Fiber section of the laboratory.

Hair and Fiber is a small section, calm and busy. The common room is stacked with boxes of evidence sent by police departments all over the country; swatches of tape that have sealed mouths and bound wrists, torn and stained clothing, deathbed sheets.

Crawford spotted Beverly Katz through the window of an examining room as he wove his way between the boxes. She had a pair of child’s coveralls suspended from a hanger over a table covered with white paper. Worki

ng under bright lights in the draft-free room, she brushed the coveralls with a metal spatula, carefully working with the wale and across it, with the nap and against it. A sprinkle of dirt and sand fell to the paper. With it, falling through the still air more slowly than sand but faster than lint, came a tightly coiled hair. She cocked her head and looked at it with her bright robin’s eye.

Crawford could see her lips moving. He knew what she was saying.

“Gotcha.”

That’s what she always said.

Crawford pecked on the glass and she came out fast, stripping off her white gloves.

“It hasn’t been printed yet, right?”

“No.”

“I’m set up in the next examining room.” She put on a fresh pair of gloves while Crawford opened the document case.

The note, in two pieces, was contained gently between two sheets of plastic film. Beverly Katz saw the tooth impressions and glanced up at Crawford, not wasting time with the question.

He nodded: the impressions matched the clear overlay of the killer’s bite he had carried with him toChesapeake.

Crawford watched through the window as she lifted the note on a slender dowel and hung it over white paper. She looked it over with a powerful glass, then fanned it gently. She tapped the dowel with the edge of a spatula and went over the paper beneath it with the magnifying glass.

Crawford looked at his watch.

Katz flipped the note over another dowel to get the reverse side up. She removed one tiny object from its surface with tweezers almost as fine as a hair.

She photographed the torn ends of the note under high magnification and returned it to its case. She put a clean pair of white gloves in the case with it. The white gloves—the signal not to touch—would always be beside the evidence until it was checked for fingerprints.

“That’s it,” she said, handing the case back to Crawford. “One hair, maybe a thirty-second of an inch. A couple of blue grains. I’ll work it up. What else have you got?”

Crawford gave her three marked envelopes. “Hair from Lecter’s comb. Whiskers from the electric razor they let him use. This is hair from the cleaning man. Gotta go.”

“See you later,” Katz said. “Love your hair.”

* * *

Jimmy Price in Latent Fingerprints winced at the sight of the porous toilet paper. He squinted fiercely over the shoulder of his technician operating the helium-cadmium laser as they tried to find a fingerprint and make it fluoresce. Glowing smudges appeared on the paper, perspiration stains, nothing.

Crawford started to ask him a question, thought better of it, waited with the blue light reflecting off his glasses.

“We know three guys handled this without gloves, right?” Price said.

“Yeah,the cleanup man, Lecter, and Chilton.”

“The fellow scrubbing sinks probably had washed the oil off his fingers. But the others—this stuff is terrible.” Price held the paper to the light, forceps steady in his mottled old hand. “I could fume it, Jack, but I couldn’t guarantee the iodine stains would fade out in the time you’ve got.”

“Ninhydrin? Boost it with heat?” Ordinarily, Crawford would not have ventured a technical suggestion to Price, but he was floundering for anything. He expected a huffy reply, but the old man sounded rueful and sad.

“No. We couldn’t wash it after. I can’t get you a print off this, Jack. There isn’t one.”

“Fuck,” Crawford said.

The old man turned away. Crawford put his hand on Price’s bony shoulder. “Hell, Jimmy. If there was one, you’d have found it.”

Price didn’t answer. He was unpacking a pair of hands that had arrived in another matter. Dry ice smoked in his wastebasket. Crawford dropped the white gloves into the smoke.

* * *

Disappointment growling in his stomach, Crawford hurried on to Documents where Lloyd Bowman was waiting. Bowman had been called out of court and the abrupt shear in his concentration left him blinking like a man just wakened.

“I congratulate you on your hairstyle. A brave departure,” Bowman said, his hands quick and careful as he transferred the note to his work surface. “How long do I have?”

“Twenty minutes max.”

The two pieces of the note seemed to glow under Bowman’s lights. His blotter showed dark green through a jagged oblong hole in the upper piece.

“The main thing, the first thing, is how Lecter was to reply,” Crawford said when Bowman had finished reading.

“Instructions for answering were probably in the part torn out.” Bowman worked steadily with his lights and filters and copy camera as he talked. “Here in the top piece he says ‘I hope we can correspond…’ and then the hole begins. Lecter scratched over that with a felt-tip pen and then folded it and pinched most of it out.”

“He doesn’t have anything to cut with.”

Bowman photographed the tooth impressions and the back of the note under extremely oblique light, his shadow leaping from wall to wall as he moved the light through 360 degrees around the paper and his hands made phantom folding motions in the air.

“Now we can mash just a little.” Bowman put the note between two panes of glass to flatten the jagged edges of the hole. The tatters were smeared with vermilion ink. He was chanting under his breath. On the third repetition Crawford made out what he was saying. “You’re so sly, but so am I.”

Bowman switched filters on his small television camera and focused it on the note. He darkened the room until there was only the dull red glow of a lamp and the blue-green of his monitor screen.

The words “I hope we can correspond” and the jagged hole appeared enlarged on the screen. The ink smear was gone, and on the tattered edges appeared fragments of writing.

“Aniline dyes in colored inks are transparent to infrared,” Bowman said. “These could be the tips of T’s here and here. On the end is the tail of what could be an M or N, or possibly an R.” Bowman took a photograph and turned the lights on. “Jack, there are just two common ways of carrying on a communication that’s one-way blind—the phone and publication. Could Lecter take a fast phone call?”

“He can take calls, but it’s slow and they have to come in through the hospital switchboard.”

“Publication is the only safeway,then.”

“We know this sweetheart reads the Tattler. The stuff about Graham and Lecter was in the Tattler. I don’t know of any other paperthat carriedit.”

“Three T’s and an R in Tattler. Personal column, you think? It’s a place to look.”

Crawford checked with the FBI library, then telephoned instructions to theChicagofield office.

Bowman handed him the case as he finished.

“The Tattler comes out this evening,” Crawford said. “It’s printed inChicagoon Mondays and Thursdays. We’ll get proofs of the classified pages.”

“I’ll have some more stuff-minor, I think,” Bowman said.

“Anything useful, fire it straight toChicago. Fill me in when I get back from the asylum,” Crawford said on his way out the door.

Chapter 14

The turnstile atWashington’s Metro Central spit Graham’s fare card back to him and he came out into the hot afternoon carrying his flight bag.

The J. Edgar Hoover Building looked like a great concrete cage above the heat shimmer onTenth Street. The FBI’s move to the new headquarters had been under way when Graham leftWashington. He had never worked there.

Crawford met him at the escort desk off the underground driveway to augment Graham’s hastily issued credentials with his own. Graham looked tired and he was impatient with the signing-in. Crawford wondered how he felt, knowing that the killer was thinking about him.

Graham was issued a magnetically encoded tag like the one on Crawford’s vest. He plugged it into the gate and passed into the long white corridors. Crawford carried his flight bag.

“I forgot to tell Sarah to send a car for you.”

“Probably quicker this way.

Did you get the note back to Lecter all right?”

“Yeah,” Crawford said. “I just got back. We poured water on the hall floor. Faked a broken pipe and electrical short. We had Simmons—he’s the assistant SAC Baltimore now—we had him mopping when Lecter was brought back to his cell. Simmons thinks he bought it.”

“I kept wondering on the plane if Lecter wrote it himself.”

“That bothered me too until I looked at it. Bite mark in the paper matches the ones on the women. Also it’s ball-point, which Lecter doesn’t have. The person who wrote it had read the Tattler, and Lecter hasn’t had a Tattler. Rankin and Willingham tossed the cell. Beautiful job, but they didn’t find diddly. They took Polaroids first to get everything back just right. Then the cleaning man went in and did what he always does.”

“So what do you think?”

“As far as physical evidence toward an ID, the note is pretty much dreck,” Crawford said. “Some way we’ve got to make the contact work for us, but damn if I know how yet. We’ll get the rest of the lab results in a few minutes.”

“You’ve got the mail and phone covered at the hospital?”

“Standing trace-and-tape order for any time Lecter’s on the phone. He made a call Saturday afternoon. He told Chilton he was calling his lawyer. It’s a damn WATS line, and I can’t be sure.

“What did his lawyer say?”

“Nothing. We got a leased line to the hospital switchboard for Lecter’s convenience in the future, so that won’t get by us again. We’ll fiddle with his mail both ways, starting next delivery. No problem with warrants, thank God.”

Crawford bellied up to a door and stuck the tag on his vest into the lock slot. “My new office. Come on in. Decorator had some paint left over from a battleship he was doing. Here’s the note. This print is exactly the size.”

Graham read it twice. Seeing the spidery lines spell his name started a high tone ringing in his head.

The Silence of the Lambs

The Silence of the Lambs Red Dragon

Red Dragon Hannibal

Hannibal Black Sunday

Black Sunday Cari Mora

Cari Mora Hannibal Rising

Hannibal Rising Red Dragon hl-1

Red Dragon hl-1 The Silence of the Lambs (Hannibal Lecter)

The Silence of the Lambs (Hannibal Lecter)