- Home

- Thomas Harris

Red Dragon hl-1

Red Dragon hl-1 Read online

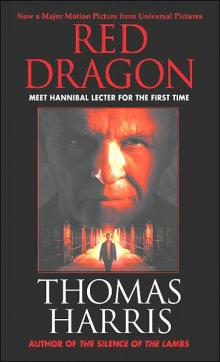

Red Dragon

( Hannibal Lecter - 1 )

Thomas Harris

In the realm of psychological suspense, Thomas Harris stands alone. Exploring both the nature of human evil and the nerve-racking anatomy of forensic investigation, Harris unleashes a frightening vision of the dark side of our well-lighted world. In this extraordinary tale—which preceded “The Silence of the Lambs” and “Hannibal,” Harris introduced the unforgettable character Dr. Hannibal Lecter. And in it, Will Graham—the FBI man who hunted Lecter down—risks his sanity and his life to duel a killer called…

The Red Dragon

A quiet summer night… a neat suburban house… and another happy family is shattered—the latest victims of a grisly series of hideous sacrificial killings that no one understands, and no one can stop. Nobody lives to tell of the unimaginable carnage. Only the blood-stained walls bear witness.

All hope rests on the Special Agent Will Graham, who must peer inside the killer’s tortured soul to understand his rage, to anticipate and prevent his next vicious crime. Desperate for help, Graham finds himself locked in a deadly alliance with the brilliant Dr. Hannibal Lecter—the infamous mass murderer who Graham put in prison years ago. As the imprisoned Lecter tightens the reins of revenge, Graham’s feverish pursuit of the Red Dragon draws him inside the warped mind of a psychopath, into an unforgettable world of demonic ritual and violence, beyond the limits of human terror.

Thomas Harris

Red Dragon

One can only see what one observes, and one observes only things which are already in the mind.

Alphonse Bertillon

…For Mercy has a human heart,

Pity a human face,

And Love, the human form divine,

And Peace, the human dress.

William Blake, Songs of Innocence (The Divine Image)

Cruelty has a Human Heart,

And Jealousy a Human Face,

Terror the Human Form Divine,

And Secrecy the Human Dress.

The Human Dress is forged Iron,

The Human Form a fiery Forge,

The Human Face a Furnace seal’d,

The Human Heart its hungry Gorge.

William Blake, Songs of Experience (A Divine Image)

Chapter 1

Will Graham sat Crawford down at a picnic table between the house and the ocean and gave him a glass of iced tea.

Jack Crawford looked at the pleasant old house, salt-silvered wood in the clear light. “I should have caught you inMarathonwhen you got off work,” he said. “You don’t want to talk about it here.”

“I don’t want to talk about it anywhere, Jack. You’ve got to talk about it, so let’s have it. Just don’t get out any pictures. If you brought pictures, leave them in the briefcase—Molly and Willy will be back soon.”

“How much do you know?”

“What was in theMiami Herald and the Times,” Graham said. “Two families killed in their houses a month apart.BirminghamandAtlanta. The circumstances were similar.”

“Not similar. The same.”

“How many confessions so far?”

“Eighty-six when I called in this afternoon,” Crawford said. “Cranks. None of them knew details. He smashes the mirrors and uses the pieces. None of them knew that.”

“What else did you keep out of the papers?”

“He’s blond, right-handed and really strong, wears a size-eleven shoe. He can tie a bowline. The prints are all smooth gloves.”

“You said that in public.”

“He’s not too comfortable with locks,” Crawford said. “Used a glass cutter and a suction cup to get in the house last time. Oh, and his blood’s AB positive.”

“Somebody hurt him?”

“Not that we know of. We typed him from semen and saliva. He’s a secretor.” Crawford looked out at the flat sea. “Will, I want to ask you something. You saw this in the papers. The second one was all over the TV. Did you ever think about giving me a call?”

“Why not?”

“There weren’t many details at first on the one inBirmingham. It could have been anything—revenge, a relative.”

“But after the second one, you knew what it was.”

“Yeah. A psychopath. I didn’t call you because I didn’t want to. I know who you have already to work on this. You’ve got the best lab. You’d have Heimlich at Harvard, Bloom at theUniversityofChicago—”

“And I’ve got you down here fixing fucking boat motors.”

“I don’t think I’d be all that useful to you, Jack. I never think about it anymore.”

“Really? You caught two. The last two we had, you caught.”

“How? By doing the same things you and the rest of them are doing.”

“That’s not entirely true, Will. It’s the way you think.”

“I think there’s been a lot of bullshit about the way I think.”

“You made some jumps you never explained.”

“The evidence was there,” Graham said.

“Sure. Sure there was. Plenty of it—afterward. Before the collar there was so damn little we couldn’t get probable cause to go in.”

“You have the people you need, Jack. I don’t think I’d be an improvement. I came down here to get away from that.”

“I know it. You got hurt last time. Now you look all right.”

“I’m all right. It’s not getting cut. You’ve been cut.”

“I’ve been cut, but not like that.”

“It’s not getting cut. I just decided to stop. I don’t think I can explain it.”

“If you couldn’t look at it anymore, God knows I’d understand that.”

“No. You know-having to look. It’s always bad, but you get so you can function anyway, as long as they’re dead. The hospital, interviews, that’s worse. You have to shake it off and keep on thinking. I don’t believe I could do it now. I could make myself look, but I’d shut down the thinking.”

“These are all dead, Will,” Crawford said as kindly as he could.

Jack Crawford heard the rhythm and syntax of his own speech in Graham’s voice. He had heard Graham do that before, with other people. Often in intense conversation Graham took on the other person’s speech patterns. At first, Crawford had thought he was doing it deliberately, that it was a gimmick to get the back-and-forth rhythm going.

Later Crawford realized that Graham did it involuntarily, that sometimes he tried to stop and couldn’t.

Crawford dipped into his jacket pocket with two fingers. He flipped two photographs across the table, face up.

“All dead,” he said.

Graham stared at him a moment before picking up the pictures.

They were only snapshots: A woman, followed by three children and a duck, carried picnic items up the bank of a pond. A family stood behind a cake.

After half a minute he put the photographs down again. He pushed them into a stack with his finger and looked far down the beach where the boy hunkered, examining something in the sand. The woman stood watching, hand on her hip, spent waves creaming around her ankles. She leaned inland to swing her wet hair off her shoulders.

Graham, ignoring his guest, watched Molly and the boy for as long as he had looked at the pictures.

Crawford was pleased. He kept the satisfaction out of his face with the same care he had used to choose the site of this conversation. He thought he had Graham. Let it cook.

Three remarkably ugly dogs wandered up and flopped to the ground around the table.

“My God,” Crawford said.

“These are probably dogs,” Graham explained. “People dump small ones here all the time. I can give away the cute ones. The rest stay around and get to be big ones.”

“They’re fat enough.”

“Molly’s a sucker for strays.”

“You’ve got a nice life here, Will. Molly and the boy. How old is he?”

“Eleven.”

“Good-looking kid. He’s going to be taller than you.”

Graham nodded. “His father was. I’m lucky here. I know that.”

“I wanted to bring Phyllis down here.Florida. Get a place when I retire, and stop living like a cave fish. She says all her friends are inArlington.”

“I meant to thank her for the books she brought me in the hospital, but I never did. Tell her for me.”

“I’ll tell her.”

Two small bright birds lit on the table, hoping to find jelly. Crawford watched them hop around until they flew away.

“Will, this freak seems to be in phase with the moon. He killed the Jacobis inBirminghamon Saturday night, June 28, full moon. He killed the Leeds family inAtlantanight before last, July 26. That’s one day short of a lunar month. So if we’re lucky we may have a little over three weeks before he does it again.”

“I don’t think you want to wait here in the Keys and read about the next one in yourMiami Herald. Hell, I’m not the pope, I’m not saying what you ought to do, but I want to ask you, do you respect my judgment, Will?”

“Yes.”

“I think we have a better chance to get him fast if you help. Hell, Will, saddle up and help us. Go toAtlantaandBirminghamand look, then come on toWashington. Just TDY.”

Graham did not reply.

Crawford waited while five waves lapped the beach. Then he got up and slung his suit coat over his shoulder. “Let’s talk after dinner.”

“Stay and eat.”

Crawford shook his head. “I’ll come back later. There’ll be messages at the Holiday Inn and I’ll be a while on the phone. Tell Molly thanks, though.”

Crawford’s rented car raised thin dust that settled on the bushes beside the shell road.

Graham returned to the table. He was afraid that this was how he would remember the end of Sugarloaf Key-ice melting in two tea glasses and paper napkins fluttering off the redwood table in the breeze and Molly and Willy far down the beach.

* * *

Sunset on Sugarloaf, the herons still and the red sun swelling.

Will Graham and Molly Foster Graham sat on a bleached drift log, their faces orange in the sunset, backs in violet shadow. She picked up his hand.

“Crawford stopped by to see me at the shop before he came out here,” she said. “He asked directions to the house. I tried to call you. You really ought to answer the phone once in a while. We saw the car when we got home and went around to the beach.”

“What else did he ask you?”

“How you are.”

“And you said?”

“I said you’re fine and he should leave you the hell alone. What does he want you to do?”

“Look at evidence. I’m a forensic specialist, Molly. You’ve seen my diploma.”

“You mended a crack in the ceiling paper with your diploma, I saw that.” She straddled the log to face him. “If you missed your other life, what you used to do, I think you’d talk about it. You never do. You’re open and calm and easy now. . .I love that.”

“We have a good time, don’t we?”

Her single styptic blink told him he should have said something better. Before he could fix it, she went on.

“What you did for Crawford was bad for you. He has a lot of other people—the whole damn government I guess—why can’t he leave us alone?”

“Didn’t Crawford tell you that? He was my supervisor the two times I left theFBIAcademyto go back to the field. Those two cases were the only ones like this he ever had, and Jack’s been working a long time. Now he’s got a new one. This kind of psychopath is very rare. He knows I’ve had…experience.”

“Yes, you have,” Molly said. His shirt was unbuttoned and she could see the looping scar across his stomach. It was finger width and raised, and it never tanned. It ran down from his left hipbone and turned up to notch his rib cage on the other side.

Dr. Hannibal Lecter did that with a linoleum knife. It happened a year before Molly met Graham, and it very nearly killed him. Dr. Lecter, known in the tabloids as “Hannibalthe Cannibal,” was the second psychopath Graham had caught.

When he finally got out of the hospital, Graham resigned ftom the Federal Bureau of Investigation, leftWashingtonand found a job as a diesel mechanic in the boatyard at Marathon in theFlorida Keys. It was a trade he grew up with. He slept in a trailer at the boatyard until Molly and her good ramshackle house on Sugarloaf Key.

Now he straddled the drift log and held both her hands. Her feet burrowed under his.

“All right, Molly. Crawford thinks I have a knack for the monsters. It’s like a superstition with him.”

“Do you believe it?”

Graham watched three pelicans fly in line across the tidal flats. “Molly, an intelligent psychopath—particularly a sadist—is hard to catch for several reasons. First, there’s no traceable motive. So you can’t go that way. And most of the time you won’t have any help from informants. See, there’s a lot more stooling than sleuthing behind most arrests, but in a case like this there won’t be any informants. He may not even know that he’s doing it. So you have to take whatever evidence you have and extrapolate. You try to reconstruct his thinking. You try to find patterns.”

“And follow him and find him,” Molly said. “I’m afraid if you go after this maniac, or whatever he is—I’m afraid he’ll do you like the last one did. That’s it. That’s what scares me.”

“He’ll never see me or know my name, Molly. The police, they’ll have to take him down if they can find him, not me. Crawford just wants another point of view.”

She watched the red sun spread over the sea. High cirrus glowed above it.

Graham loved the way she turned her head, artlessly giving him her less perfect profile. He could see the pulse in her throat, and remembered suddenly and completely the taste of salt on her skin. He swallowed and said, “What the hell can I do?”

“What you’ve already decided. If you stay here and there’s more killing, maybe it would sour this place for you. High Noon and all that crap. If it’s that way, you weren’t really asking.”

“If I were asking, what would you say?”

“Stay here with me. Me. Me. Me. And Willy, I’d drag him in if it would do any good. I’m supposed to dry my eyes and wave my hanky. If things don’t go so well, I’ll have the satisfaction that you did the right thing. That’ll last about as long as taps. Then I can go home and switch one side of the blanket on.”

“I’d be at the back of the pack.”

“Never in your life. I’m selfish, huh?”

“I don’t care.”

“Neither do I. It’s keen and sweet here. All the things that happen to you before make you know it. Value it, I mean.”

He nodded.

“Don’t want to lose it either way,” she said.

“Nope. We won’t, either.”

Darkness fell quickly and Jupiter appeared, low in the southwest.

They walked back to the house beside the rising gibbous moon. Far out past the tidal flats, bait fish leaped for their lives.

* * *

Crawford came back after dinner. He had taken off his coat and tie and rolled up his sleeves for the casual effect. Molly thought Crawford’s thick pale forearms were repulsive. To her he looked like a damnably wise ape. She served him coffee under the porch fan and sat with him while Graham and Willy went out to feed dogs. She said nothing. Moths batted softly at the screens.

“He looks good, Molly,” Crawford said. “You both do—skinny and brown.”

“Whatever I say, you’ll take him anyway, won’t you?”

“Yeah. I have to. I have to do it. But I swear to God, Molly, I’ll make it as easy on him as I can. He’s changed. It’s great you got married.”

“He’s

better and better. He doesn’t dream so often now. He was really obsessed with the dogs for a while. Now he just takes care of them; he doesn’t talk about them all the time. You’re his friend, Jack. Why can’t you leave him alone?”

“Because it’s his bad luck to be the best. Because he doesn’t think like other people. Somehow he never got in a rut.”

“He thinks you want him to look at evidence.”

“I do want him to look at evidence. There’s nobody better with evidence. But he has the other thing too. Imagination, projection, whatever. He doesn’t like that part of it.”

“You wouldn’t like it either if you had it. Promise me something, Jack. Promise me you’ll see to it he doesn’t get too close. I think it would kill him to have to fight.”

“He won’t have to fight. I can promise you that.”

When Graham finished with the dogs, Molly helped him pack.

Chapter 2

Will Graham drove slowly past the house where the Charles Leeds family had lived and died. The windows were dark. One yard light burned. He parked two blocks away and walked back through the warm night, carrying theAtlantapolice detectives’ report in a card-board box.

Graham had insisted on coming alone. Anyone else in the house would distract him—that was the reason he gave Crawford. He had another, private reason: he was not sure how he would act. He didn’t want a face aimed at him all the time.

He had been all right at the morgue.

The two-story brick home was set back from the street on a wooded lot. Graham stood under the trees for a long time looking at it. He tried to be still inside. In his mind a silver pendulum swung in darkness. He waited until the pendulum was still.

A few neighbors drove by, looking at the house quickly and looking away. A murder house is ugly to the neighbors, like the face of someone who betrayed them. Only outsiders and children stare.

The shades were up. Graham was glad. That meant no relatives had been inside. Relatives always lower the shades.

The Silence of the Lambs

The Silence of the Lambs Red Dragon

Red Dragon Hannibal

Hannibal Black Sunday

Black Sunday Cari Mora

Cari Mora Hannibal Rising

Hannibal Rising Red Dragon hl-1

Red Dragon hl-1 The Silence of the Lambs (Hannibal Lecter)

The Silence of the Lambs (Hannibal Lecter)